Russia Mastered Drone-Proofing Its Tanks—Ukraine Is Copying Its Tricks

It took years and tens of thousands of casualties, but the Russians have learned to innovate

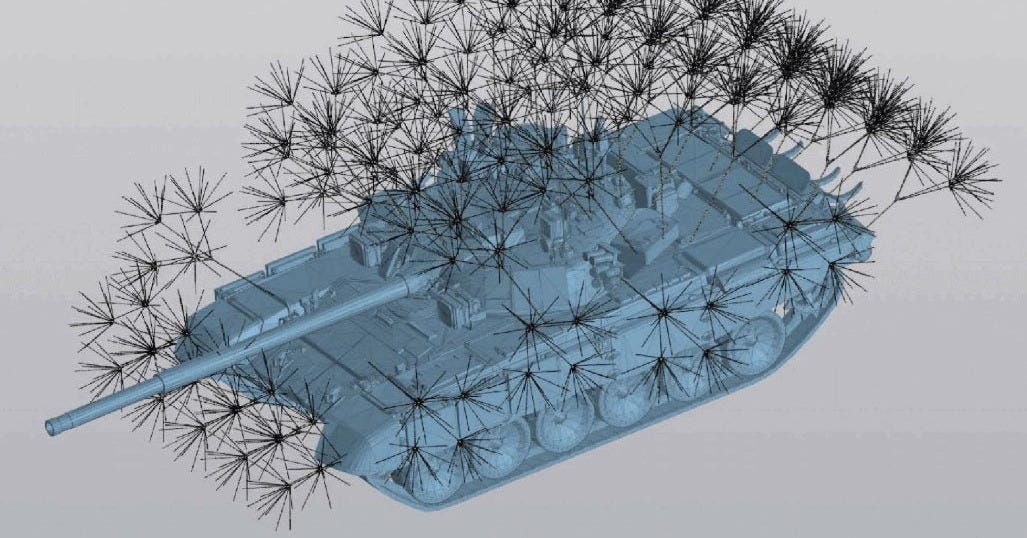

Russian anti-drone hedgehog armor for combat vehicles is ugly, but it works

Thousands of metal wires, welded to an add-on metal frame, can detonate incoming drones at a safe distance

Ukrainian forces have begun copying the hedgehog design for their own vehicles

It’s apparent by now that the Russians are the leading innovators of anti-drone protection

Back in November, Russian forces began welding thousands of metal wires to metal frames and bolting these frames onto armored vehicles. This so-called “hedgehog armor,” produced from unwound aluminum cabling, is the latest anti-drone innovation in daily use ... at least until the newest “dandelion armor” makes its first appearance along the front line.

Two months after the Russians pioneered the approach, a Ukrainian unit has welded hedgehog protection to an American APC—the second type of such armor to appear on the front.

The armor marks another Russian lead in the counterdrone race. After two years of getting slaughtered by Ukrainian FPV drones, Russian forces have become the war’s leading innovators in vehicle protection—one factor behind their slow but steady territorial gains since 2024. Ukrainian units are now copying the designs.

Hedgehog armor looks ridiculous. From a distance, it has the appearance of hair—as though a vehicle is wearing a bulky, badly made wig.

But the armor works. The wires, which protrude a foot or more from their frame, can detonate incoming first-person-view drones a safe distance from a vehicle’s hull. It may not defeat every drone, but it doesn’t have to. By now, most Russian vehicles have layer upon layer of add-on anti-drone protection.

It’s telling that more Ukrainian units are adding hedgehog armor to their own vehicles. A video that circulated online recently depicts an American-designed M-113 armored personnel carrier with all-around hedgehog protection installed on a metal cage that also offers its own protection.

“Such extra material is pretty heavy,” Canadian drone expert Roy pointed out, “but the old vehicle seems to handle it easily.”

Up-armored M-113s represent at least the second Ukrainian hedgehog type to appear near the front. The first was a tank.

Russian innovations

That the Russians have become the world’s leaders in counterdrone improvisation speaks to a profound shift in Russian military culture that has slowly occurred in the 46 months since Russian widened its war on Ukraine.

In the first two years of the war, the Russians were guilty of institutional lethargy. Riding into battle in long columns of under-protected and under-supported tanks and infantry fighting vehicles, they were dealt humiliating defeats by nimbler—and fast-adapting—Ukrainian forces supported by thousands of FPV drones every month.

It took time and tens of thousands of casualties, but the Russians shrugged off the strictures of bureaucracy and outdated doctrine and, in early 2024, began adapting in haste.

They armed their warplanes with cheap precision glide bombs, began mass-producing inexpensive Shahed attack drones, and broke up unwieldy assault groups into smaller and harder-to-spot formations riding in whatever fast vehicles were available.

Alone, each development may have stank of desperation. Together, they pointed to a new culture of innovation that has transformed the Russian military. “Russian adaptations have aggregated,” the Royal United Services Institute noted in February 2025.

One of the most obvious signs of this new willingness to learn and change was the first appearance, in the spring of 2023, of the so-called “turtle tank”—an armored vehicle, usually an older tank, fitted with layers of metal sheeting.

There’s no single turtle tank design. Russian regiments build their own turtles based on hard lessons they’ve learned in actual combat. At least one Russian marine brigade is even welding old shipping containers onto some tanks as a counterdrone expedient.

The metal shells are ungainly and limit a tank’s mobility. But they also help a vehicle survive multiple drone strikes: sometimes dozens of scores of them. Turtles are “a very particular solution to a very particular problem,” Mick Ryan, a retired Australian army general, wrote for the Lowy Institute in Sydney.

Read the rest at Euromaidan Press.